R. Vaishno Bharati

IT for Change, IndiaVaishno works as the Project Associate at IT for Change. Her work focuses on the programmatic aspects of the online magazine Bot Populi’s feminist track. She also contributes to the research and advocacy of national and international projects undertaken by the organization and frequently writes for Bot Populi.

In May 2019, after India had re-elected the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government for a second term, the hashtags #ModiSwearingIn and #ModiSarkar2 were trending on Twitter India – hashtags aimed at bringing attention to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his new government.

At the same time an innocuous-sounding (and seemingly completely unrelated) meme hashtag #PrayForNaesamani quickly took over as the top trend in the country.

The meme was created when a Facebook group called Civil Engineering Learners posted a picture of a hammer along with the question, “What is the name of this tool in your country?” One respondent replied with a scene from a popular Tamil feature film Friends where a fictional character called “Naesamani” is hit on the head with a hammer. When another Facebook user jokingly responded with, “Is he OK?”, a meme was born.

Over time, #PrayForNaesamani was being tweeted and retweeted by celebrities, brands, corporations, and others. Many speculated that people in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu drove the meme’s popularity to divert attention from the trending hashtags around Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s swearing-in ceremony.

It ultimately became the number one trend in India on Twitter, and also the second largest trending hashtag worldwide.

The above is an example of how unrelated, absurdist, and humorous memes have in the recent past been repurposed into signs of dissent and resistance. Through collective and connective action, memes are used by organisations and individuals to initiate political change. Collective action, requiring centralised coordination, has always been carried out by large organisations with significant amount of resources. However, connective action, established through the voluntary sharing of personalised content in networked publics (ex. Occupy Wall Street), has prevailed in the face of authoritarian policing and the narrowing scope of civil society organisations.

The democratising nature of the internet and omnipresence of memetic discourse have contributed to a multi-voiced, participatory citizenship.

Dissent Through Political Memes

Memes, whether political or otherwise, are fundamentally about expression and are used as a means of establishing relatability with others. As effective “units of persuasion” within the attention economy, memes help indicate political affiliation and have the ability to realign political discussions. Memes can thus be used to build narratives and organise communities around those narratives. This can be particularly empowering for marginalised groups seeking to shift public discourse in their favour.

Furthermore, participants of online movements are inspired by, borrow from, and respond to memetic strategies that have preceded theirs. Templates, such as #BlackLivesMatter (#BLM), are built upon and adapted to different contexts to better reflect local issues. For instance, #BLM was modified to #DalitLivesMatter in India, highlighting systemic caste-based oppression and #PapuanLivesMatter in Indonesia, calling attention to discrimination against indigenous Papuans. Lockdowns notwithstanding, it was used by people in Brazil, South Africa, and Australia, among other places, to congregate and draw attention to post-colonial racism and discrimination in their countries.

However, the contextualisation of memes can also completely re-write the meaning and symbolism of a meme. For instance Pepe the frog, was removed from its alt-right ties in the West and re-appropriated for it is frustrated or sad expression by Hong Kong protestors.

Memes can simplify complex political issues through humour and emotion and act as conduits of political expression. The use of memes can offer affective affirmation regarding an issue and help reach out to others with similar political ideologies, building camaraderie and solidarity in online publics.

The three-finger solidarity salute, popularised in the Hunger Games book and movie franchise was first adopted as a symbol of resistance in Thailand. It was later used by protestors in Hong Kong and Myanmar. The gesture was made viral through posting and re-posting online, encouraging pro-democracy advocates to collectivise and occupy both online and offline spaces.

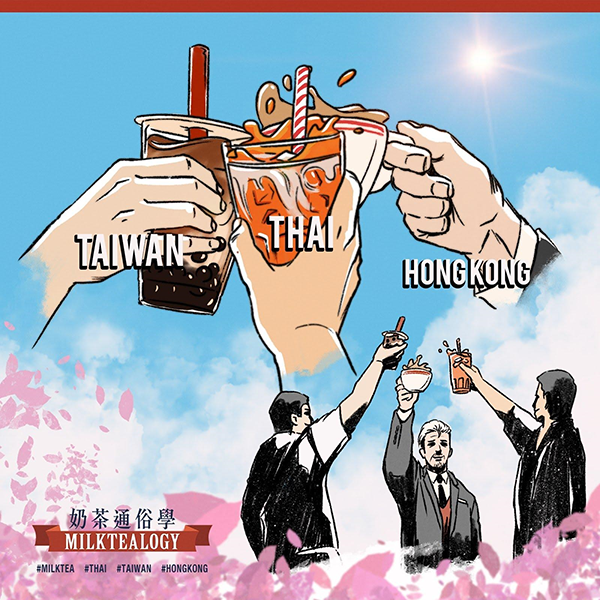

Another example is the birth of the #MilkTeaAlliance – a loose, transnational network of youth who see themselves as engaged in similar fights against authoritarianism. Youth in Thailand, Hong Kong and Taiwan (and now including Myanmar, India, and Indonesia) adopted the common symbol of Milk Tea (a beverage popular in the region) as a unifying symbol for those in the region undergoing similar civil society upheavals.

Circumventing State Censorship

Many governments around the world use peer-to-peer networks and memetic tactics to bombard people with pro-government narratives while simultaneously censor opinions against the state. However, the very nature of memes makes censorship difficult.

Dynamic, short-lived, and always a work in progress, there is no ‘final’ form that a meme takes due to contextual repurposing and overwriting. Since they are a collective exercise, memes are also tough to attribute to a single author or creator.

Memes that take the form of parodies and mash-ups have the added ability to evade censorship through the use of silly, absurdist humour. In fact, the ‘silly’ has often been used to express ‘serious’ ideas through the tactical use of puns, images, coded language and in-jokes that even circumvent precise censorship methods. Additionally, humour is akin to a “digital analgesic” (pain reliever) that helps advance the core argument of a meme. When used to convey a sense of irony, humour questions authority and political omnipotence, as it demystifies power and the facade of competence.

Conclusion

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, most of our everyday activities including resistance movements and activisms have moved online. Some of these changes will likely stay in the post-pandemic world. This is not to say that all forms of protests will, or should, move to the digital sphere, but tapping into the resources of memetic discourse offers us another avenue for dissent. The interlinking of online and offline spaces and cultures is more pronounced now than ever before.

We need to use every arrow in our quiver to counter institutions with a lot more power and resources at their disposal. Memes have become a part of contemporary resistance language; they are sites for battling ideological differences, quick and easy to produce and spread, and fairly robust against censorship due to their high mutability. Harnessing the power of these digital palimpsests can go a long way in enabling social activists to initiate greater and better political action.